Supply Chain Continuity Management (SCCM)

The dependencies on supply chains are constantly increasing for many companies...Dependence is on the rise

The dependencies of supply chains are constantly increasing for many companies, regardless of whether they involve the supply of raw materials or goods, services or outsourced processes. The size of this network of suppliers is impressively shown by the example of VW: The company estimates its suppliers and service providers in April 2020 at over 40,000, plus hundreds of forwarding agents.

Well, if all the links in the chain interlock and everything runs like clockwork! And what if it doesn't? What do you do if a supply chain breaks down and critical goods do not arrive? Then the measures of Supply Chain Continuity Management (SCCM) come into play.

Reasons for supply chain failure

Supply chains can be interrupted by a wide variety of events. If we look at the area of manufacturing companies, the examples are particularly diverse:

- Delivery failures and difficulties due to Corona, as production and commodity flows come to a standstill or only run at a reduced pace

- Fixed freighters, as recently in the Suez Canal, which stop the transport of goods for weeks

- Vessels hijacked by piracy

- Supplier bankruptcies

- Machine breakdowns

- Cyber attacks

- Natural disasters

- Volcano eruptions, as in Iceland in 2010, … – the list is more than long.

Complexity

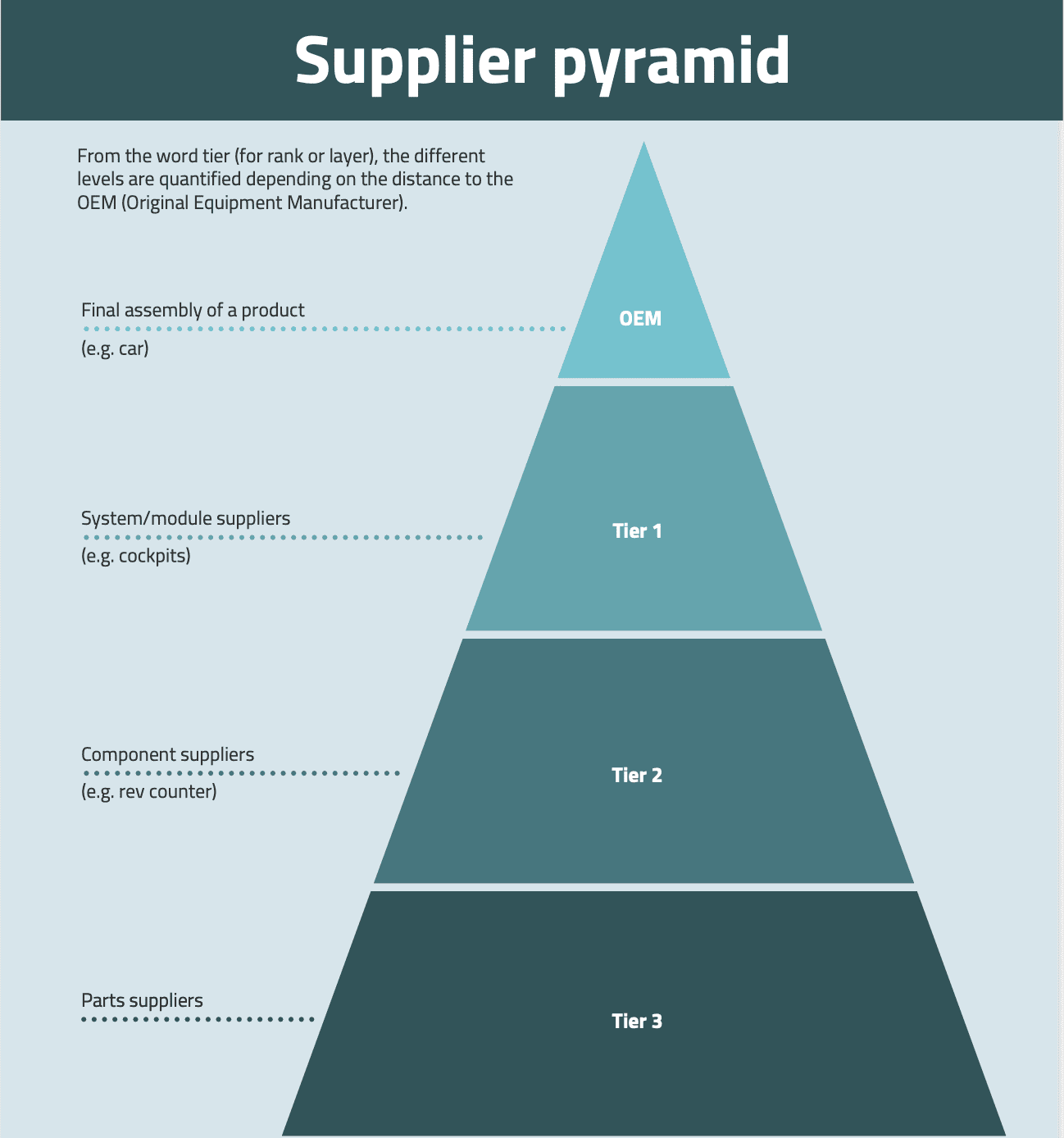

What must not be forgotten here is that suppliers also have subcontractors. In supplier pyramids, suppliers are referred to as Tier 1, Tier 2, etc.

As shown in the diagram, the lower tier supplies the one above with products that are further processed by the supplier. The flow is from the OEM downwards. If you think about possible interruptions in the supply chain, it quickly becomes clear that the cause that affects you later may have originated several supply levels earlier.

In general, supply chains are becoming more complex and often more global – and therefore more complex and opaque. It is a challenging task, but every company should have a complete overview of its supply chains and their risks in order to be able to react proactively in case of defaults or delays. Prevention is better than cure, because those who are not prepared will not only lose money but also suffer reputational damage. And making up for this damage is more than twice as difficult and also much more protracted than making an effort to have an SCCM tailored to the company.

CRITIS

In Germany, certain companies are subject to regulations on how to deal with a failure in order to ensure a quick restart and thus a supply of the population. Critical infrastructures include utilities (gas, water, electricity), financial service providers, telecommunications providers and other sectors. In order to secure supply chains, they must first be analysed and evaluated. It is important to identify the potential impact of disruptions and to manage them.

SCCM and BCM

In BCM, the focus is on defining procedures that ensure the fastest possible restart of time-critical processes. In the case of SCCM, the focus is on restarting supply chains.

One component of the SCCM is to create a supply chain map to get an overview of all existing supply chains. The result is a global map of the existing supply network and the associated documentation of material origin, all transports and so on. This analysis alone can reveal possible risks as well as opportunities to hedge against them.

Building an SCCM

For the construction of the SCCM, the results of the restart times of the processes from the BIA, which was carried out in the context of BCM, are used. The supplier-related data from the BCM risk assessment are checked to see whether all risks have really been taken into account. The risk analysis of the suppliers then deals with the following questions, for example:

How high is the risk...

- ...of insolvency?

- ...of an interruption in transport?

- ...an interruption due to changing laws (customs, import regulations)?

- ...the termination of the contract by the supplier?

- ...of a delivery failure due to local environmental influences/forces of nature?

How can a company proceed to avoid being affected by interruptions? If a company has only one supplier for a product, it can consider increasing its own stock. If there are several sources of supply for a product, it is possible to expand the supply network. In this case, it would be advisable to order the product from its suppliers on a permanent rotating basis in order to know the quality and to be able to be supplied as quickly as possible in case of failure. However, the decision to secure the supply chain via alternative suppliers also means that these must be examined with regard to the risk of failure. Alternatively, it may be possible to outsource the manufacture of the product to your own company in order to protect yourself against a supply failure. Another option would be to work more closely with the supplier in order to react jointly to imminent failures and thus bring more stability into the supply chain.

Sustainable strengthening of resilience

The most sustainable step is to transfer the obligation of uninterrupted supply to the supplier, i.e. to encourage the supplier to implement BCM (and the supplier to implement BCM with its suppliers!) and thereby build a partnership. This cooperation may even offer attractive marketing opportunities, as it increases the resilience of the supply chain as a whole and thus also the company's own attractiveness to potential customers. However, things get complicated again if the supplier is larger and more marketable and thus does not accept proposals and/or contractual obligations because the market value of its customer is too low.

Conclusion

Whatever it may look like: If the „saving measures“ in SCCM have been determined, these must be checked at regular intervals. If the supplier has implemented BCM, this must be checked intensively every year for critical suppliers through audits and/or the collection of documentation. At best, the supplier in turn also encourages its suppliers to implement BCM. For less critical supply chains, the controls can be softer.

SCCM, like BCM, has a lifecycle that has to be maintained and checked again and again. Not least because there are always small (and/or large) changes in the area of goods flows and outsourced processes and services. In the course of this, one would also notice, for example, that critical products might change. An A- may become a C-, a B- an A-product, etc. These changes are particularly complex in the market segment of computer chips, for example, which are constantly being developed further by the manufacturers and thus frequently changed. This also makes it clear that progress alone is putting pressure on SCCM in some sectors.

In order to be prepared for new suppliers, a questionnaire or checklist should be developed to find out what means the potential supplier uses to counter disruptions in its supply chain. In addition, reliability and on-time delivery play a major role, as well as transparency on how previous difficulties have been dealt with. If there is a Supply Chain Management and/or Strategic Purchasing department in the company, there is already a lot of information on these topics. Finally, as suppliers are also interested in a good economic relationship, it is an idea to involve them in new processes/product developments, for example. In general, it is advisable to fix all points concerning product quality, inspections and audits in contracts with suppliers.

A blanket agreement with suppliers is a good idea.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to SCCM, but there is a perfect approach for every case to provide assurance. The Controllit AG will be happy to advise you on this.